For hundreds of years, the prevailing narrative of Australia’s history was told through the narrow lens of white colonialism.

Truth-telling brings forward First Nations voices and experiences. It involves honest, and sometimes uncomfortable, conversations about Australia's history. In the context of colonial history, much has been written about early colonisers including William Wyatt. Wyatt sought to improve his economic and social standing, which he knew would be more easily achieved in the new colony of South Australia.

But what of the experiences of the Aboriginal peoples of what became known as South Australia?

The timeline below has been created directly from research completed in 2023 by Dr Jennifer Ampetyane Caruso, an Eastern Arrernte woman, that examined Wyatt's time in the colony and his interactions and influence on the lives of Aboriginal peoples. As such, it only includes items addressed in Dr Caruso's research, and some years are unaccounted for, but we hope it opens the door to a more truthful telling of Wyatt's time in the colony.

We thank Dr Caruso for applying an Aboriginal perspective and for the generosity of spirit demonstrated in reviewing what was at times distressing material.

The language and terminology below has been taken from historical records and used with the intention of recording accurate accounts of past events. It is not used here to offend, but to convey the language used by colonisers in positions of power at the time.

While this information is depicted in a chronological timeline, we acknowledge that history is not linear for Aboriginal peoples. Each event, experience or story is interwoven with others, and this timeline seeks only to shine a light on what we know about Dr William Wyatt during his time here.

Borough of Plymouth, Engraved by John Cooke - 1820. Published April 15, 1820, by Mr(s) E. Nile, No. 48, Union Street, Stonehouse. (Picture courtesy of the Plymouth Library Services)

William and Julia Wyatt set sail from Plymouth having made the decision to emigrate to the new colony of South Australia.

Wyatt’s application for a medical post in South Australia was unsuccessful, but he was appointed the ship’s surgeon aboard the John Renwick which facilitated his passage to Adelaide.

John Renwick (From an original painting by John Ford OAM F.A.S.M.A.)

R.H. Shaw (Aboriginal corroboree, South Australia) 1891. South Australian Government Grant 1949 (Picture courtesy of the Art Gallery of South Australia)

William and Julia Wyatt arrive on Kaurna Land at Holdfast Bay.

At the time of European contact, the Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains reportedly numbered about 700.

Early colonisers report seeing the land across the plains being consumed by fire.

It was a grand and fearful sight, we were told it was a signal for the native clans to gather for the purpose of destroying the white intruders and we sat on deck all night long expecting to see bands of naked savages coming down on us. Unfortunately, many of us were filled with a lasting dread of aboriginals, and for the first few months the whole settlement of Adelaide kept watch against a ‘black attack’ which never came.

The journal of Pastor Finlayson from the John Renwick

Controlled fire and its ceremony was [Aboriginal peoples'] main [land] management tool (digging sticks were second, dams and canals third). To burn improperly was sinful… Fire was a totem. Whoever lit it answered to the ancestors… fire was work for senior people, usually men. They were responsible for any fire, even a campfire, lit on land in their care. They decided which land would be burnt, when, and how, but in deciding obeyed strict protocols with ancestors, neighbours and specialist managers.

Bill Gammage, The Adelaide District in 1836

Poster issued by the South Australian Colonization Commissioners inviting applications for the first 437 land orders, 1835. (Picture courtesy State Records of South Australia, GRG48/11)

William Wyatt begins purchasing land for himself and third parties via land auctions.

The purchase of town acres from the South Australian Company gave Wyatt land for his personal use, as well as a means of earning income as a land agent authorised to purchase land on behalf of others.

Both of Sections 150 and 93B are shown on the State Library: The District of Adelaide, South Australia Cartographic map.298 Image 25: Colonial map 93B (now known as Kurralta Park) was a regular campsite for Aboriginal people and families including Tommy Poltpalingada Booboorowie Walker.

William Wyatt spends over a week at Ramong Encounter Bay in April 1837, concerned about the high incidence of venereal disease.

He remained in Ramong Encounter Bay:

…for the purpose of inquiring into a virulent disease existing among the natives, and if possible to afford them some means of cure...

Mr Wyatt says, concerning this disease writing [in his report]: From information obtained at different times and from various sources, I think it more than probable that a venereal disease has occasionally been contracted from the whites…

The Chronicle

Studio portrait of three men from Ramong Encounter Bay, South Australia circa 1860. (Picture courtesy of the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, UK)

William Wyatt is appointed as Ad-Interim Protector of Aborigines in August 1837.

Wyatt’s appointment earns him a salary of £250 per annum.

Dr Caruso notes:

Wyatt himself at the time of discussions before his appointment stated clearly that he was more than willing to live among the blacks and that it would suit his personal scientific interests. It was recorded that Wyatt insisted that living amongst the natives would cause him little grief inasmuch as it would enable Mr Wyatt to follow out fully his botanical and entomological pursuits.

That Wyatt's focus would lean towards his 'scientific' pursuits and that he felt an imperative to examine Aboriginal people as zoological specimens rather than focusing on the needs of the people who he was charged with both protecting and providing for is disturbing…

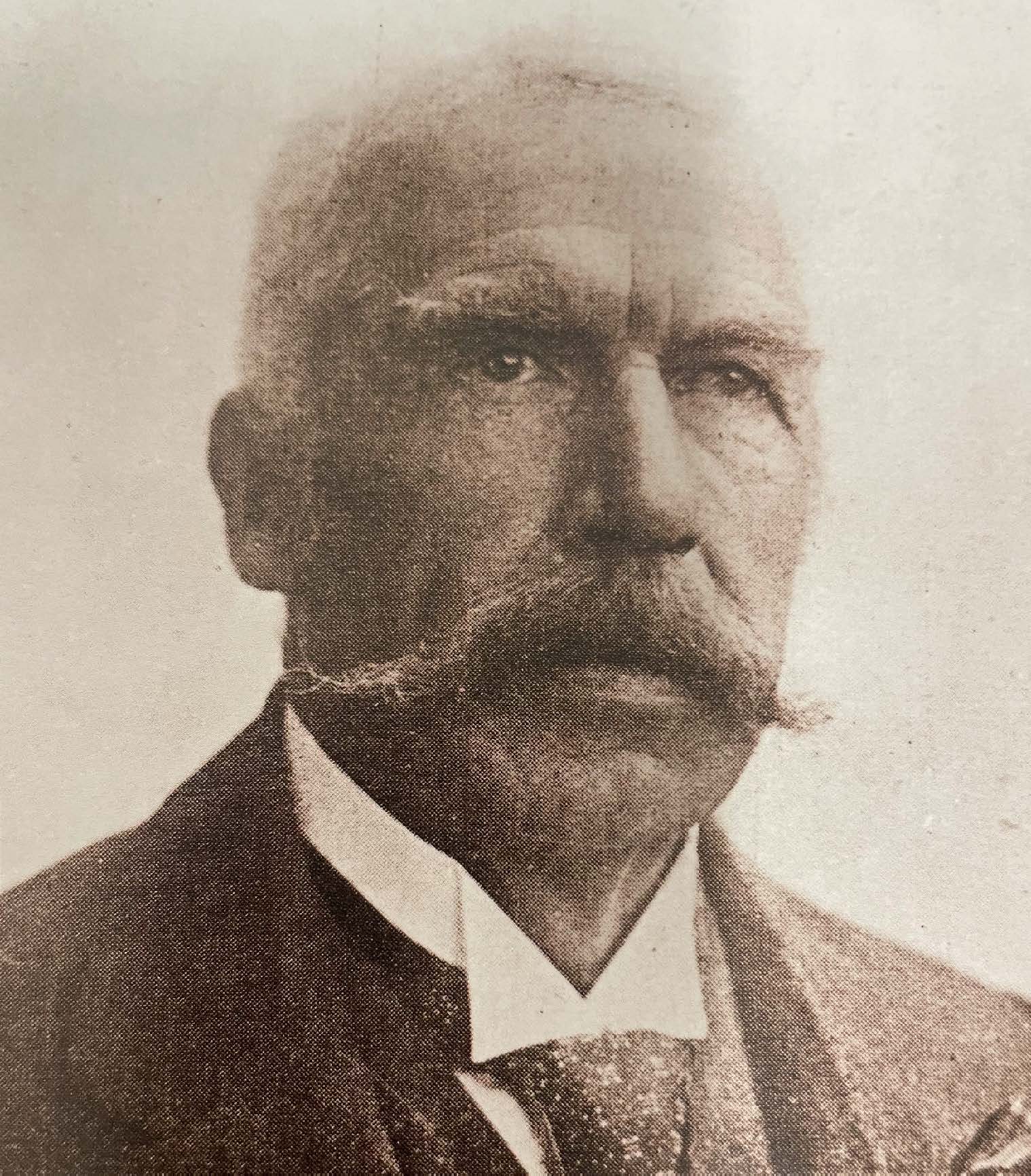

Dr William Wyatt, circa 1870

William Wyatt is called to practice his commitment to Aborigines in August 1837 after a whaler was murdered by a Ramindjeri man in Ramong Encounter Bay.

Ramindjeri man Reppindjeri was accused of murdering whaler John Driscoll, with Wyatt determining he should indeed stand trial.

Wyatt recorded that:

The circumstances surrounding the murder where the whaler began to ‘interfere indecently with the women’ needed to be included: ‘…it is incumbent on me to observe that the criminal connection of the majority of whalers… with the native women has in a very great degree been the cause of this unhappy occurrence…

This case is noted as one of the first in the colony where there were no mechanisms in colonial law for prosecuting Reppindjeri.

The immediate difficulty was occasioned by the fact that the only witnesses to the slaying were Reppindjeri’s wives, but under British law, their evidence was not valid since, being ‘heathens’, they could not take the oath…

Wyatt continued to argue in support of Reppindjeri writing of the criminal connection of the whalers and their treatment of Aboriginal women ‘…if such disgraceful practices be continued, may operate strongly upon the minds of the natives to the injury of the colonists at large…’

Conquest of the Ngarrindjeri

According to Dr Caruso this is:

...probably the most singular occasion where recognising that Aboriginal people should have rights under British colonial law was unwittingly Wyatt’s greatest moment [of] advocacy.

A view of the country and temporary erections near the site of the proposed town of Adelaide in South Australia, 1837-1838. Christine Margaret MacGregor Bequest 1975 (Picture courtesy of the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide)

A more permanent settlement is established on the south side of Karrawirra Pari River Torrens where it was anticipated Aboriginal people would settle.

Bromley’s Camp, as the settlement was called, was on the land of what is now known as Bonython Park. An acre of land was fenced off and contained 12 huts for about 200 Aboriginal people. It was at this location that rations were distributed, and missionaries began to record Kaurna language and teach Christianity to Kaurna people.

Martha Berkeley, Australia, 18 August 1813 - 7 July 1899, The first dinner given to the Aborigines 1838, Adelaide, watercolour on paper, 37.5 x 49.5 cm; Gift of J.P. Tonkin 1922 (Picture courtesy of the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide)

Distributing rations is a key role of the Protector.

The long-term effect of the disappearance of traditional foods and introduction of processed foods underpins health inequities experienced by First Nations people to this day.

Wyatt considered the distribution of rations:

An act of common justice to those whose lands we have occupied and whose game we have destroyed...

Wyatt to Colonial Secretary

Rations were also used to entice Kaurna men and women to engage in labour:

[The Aborigines] may receive, not gratuitously, but in exchange for an equivalent in the form of labour, food and clothing superior to their ordinary means of subsistence… the value of the moderate quantity of work they will be required to perform will exceed the value of the rations and clothing they will receive; and thus they asylums for the Aborigines… are a source of revenue rather than of expense.

1836-37 Colonisation Commission Report

In January 1838 a public meeting is held where it is decided a committee will be formed to assist the Protector.

The Aborigines Committee consisted of six colonists and six government officials and was designed to:

...settle all questions or differences that may arise between the Colonists and Native population and to make recommendations to the government on how best to cater to the perceived needs of the Kaurna people.

Secretary Aborigines Committee

The Committee determined that the government through the office of the protector:

...was to provide two meals per day to any Aboriginal person who chose to accept it, in order to ‘inculcate in them domestic habits, and to attach them to the location fixed upon.

Robert Foster, An Imaginary Dominion

By November 1838 the Aborigines Committee was disbanded, leaving Wyatt without a government-appointed body to advocate for the wellbeing of those in his protectorate.

Wyatt’s Holdings 1886

Before a final decision is made on the location of the capital city, William Wyatt purchases land in Kallinyalla Port Lincoln and Goorilyali Boston Island in February 1839.

Wyatt did not travel to Kallinyalla Port Lincoln himself to observe or record the situation regarding First Nations people in the region and there is no indication his interests extended beyond his land holdings. He was still the owner of these lands at the time of his death.

Wyatt had also purchased land in the Ramong Encounter Bay area in anticipation of it also being a potential site for the captial city.

Sketches by Samuel Thomas Gill (1818-1880) showing crowds gathered in Adelaide’s parklands for an Agricultural and Horticultural Show in

1845.

(Pictures courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B3696, SLSA: B16066)

The location of the Aboriginal settlement is moved to Pirltawardli on the north side of the river in March 1839.

Dr Caruso outlines, because Pirltawardli was a Kaurna ceremonial site, the decision was made that this would be a suitable move and Kaurna Meyunna would be comfortable there. But no Aboriginal peoples, then or now, would camp on a ceremonial site that considered ‘secret’ and/or sacred in nature.

It was likely that Wyatt had petitioned the government to move the settlement to this new site as Bromley’s Camp would, as Dr Caruso notes: ...interfere with the extension of the fledgling Botanic Gardens which were to be established at the western end of North Terrace.

During his time as Ad-Interim Protector of Aborigines (1837-39), William Wyatt surveys land and records Kaurna language.

Wyatt’s attempts to have sections of land reserved for Kaurna people were unsuccessful.

Through the 1836 Letters Patent, the colonial office clearly stated that there needed to be recognition of Aboriginal occupation of the land, and that it was the duty of the office of the Protector to seek the quarantine of sections of land where the Kaurna would be ‘housed’ and taken care of.

However, the South Australia Act 1834 determined that the land contained within the prescribed latitudes and longitudes were ‘waste and unoccupied’ holding colonial legal precedence of the Letters Patent.

His efforts to record Kaurna language resulted in the 1879 publication of ‘Some Account of the Manners and Superstitions of the Adelaide and Encounter Bay Aboriginal Tribes’.

William Wyatt is relieved of his position as Ad-Interim Protector of Aborigines in June 1839.

The discharging of Wyatt was grounded in the argument that:

Wyatt was supine, indifferent, neglectful and much evidence was presented to the government by a committee of colonists. While there was a long list of Wyatt’s failings and shortcomings in the role, the central sticking point was that he had not resided among the Aborigines.

Papers of Dr Alfred Austin, London & South Australian Government Gazette

There were also assertions that Wyatt, rather than attending to his duties, was cementing his place with the colonial powerbrokers:

Was not Mr Wyatt, during all this time, a member of local committees, and visiting at Government House, and practicing his own lucrative profession?

Southern Australian , 1839

Dr Caruso notes that:

Over the following years, Wyatt was appointed to very influential positions, and in time gained membership in what could be termed a ‘brotherhood’ – a small group of people who would carry out the business of consolidating the province.

Portrait of Dr William Wyatt, presented to him by the Licenced Teachers Association on his retirement as inspector of schools in June 1874, assumed to have been painted by John A. Upton (1850-1882)

Kaurna People, Adelaide

(Picture courtesy The State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B49504A)

William Wyatt is called to give evidence to the Select Committee on Aborigines in October 1860.

The purpose of this Committee was to:

Take evidence and report on the present condition of the natives, and to suggest means by which that condition may be ameliorated… and in considering the responsibility of this community to the Aboriginal inhabitants of the country of which we have taken possession, the Committee have endeavoured to elicit the opinion of the several witnesses as to the condition of its occupants when we first took possession, as compared with their present state.

Report of the Select Committee of the Legislative Council upon the Aborigines, 1860

In reviewing William Wyatt’s evidence to the Committee, Dr Caruso notes that by this point his views on Aboriginal people had changed and his role in assisting their plight was significantly diminished.

When asked during his testimony if in travelling ‘through the country in the performance of your duty’ have you had the opportunity of seeing [Aborigines], Wyatt responded that he had ‘seen very little of them’ in recent years, indicating that although there would have been Aboriginal people in plain sight, he personally had no interest or focus on them.

When asked if he had any suggestions for ‘any improved system for the management of the Aborigines’ Wyatt had none to give, making it clear he considered the fate of Aboriginal people to be no longer his responsibility.

When questioned on his views as to the ‘intelligence of the true Aborigines with the intelligence of the half-caste children’ and his suggestions for ‘any system that might be applicable to half-caste children’ his reply was: ‘I never came in contact with half-caste children, except just for a moment,’ and that, ‘If it were possible to remove them from the natives, then a beneficial influence might be exercised over them.’

The Adelaide Hospital, designed by George Kingston and built by Benjamin Fuller in the parklands near Hackney Road, opened February 1841. (Picture courtesy The State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B43330)

Adelaide Hospital Entrance, c.1880

(Picture courtesy The State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B7868)

Edward Charles Stirling (1848-1919), Wyatt Collection

The cover of Native Tribes of South Australia, Wyatt Collection

From his earliest days in the colony until his death in 1886, William Wyatt was closely involved with the medical and civic institutions being established.

This included the initial ‘Infirmary’, Medical Board, and Adelaide Hospital. He served as Coroner of the colony and held other influential positions such as Member of the Board of Governors for the South Australian Institute which was to include a public library, museum and art gallery.

Dr Caruso’s research notes that Wyatt was:

...centrally positioned to have full knowledge of the activities and practices of all the medicos who were registered by the Medical Board and were in practice.

From 1875 Wyatt was closely associated with Sir Edward Charles Stirling, who returned to the colony after studying to be a surgeon in England. Stirling and Wyatt collaborated on topics such as ‘anthropology, palaeontology, zoology, horticulture and public health.’ Stirling ultimately saw the South Australian Museum as his major life’s work, for which the collection and recording of Aboriginal people was a key practice.

In 1879 Wyatt wrote:

The sanguine expectations… in regard to the civilisation of the natives, have been doomed to disappointment… and the probable precursor of complete annihilation of the race, increase the interest in establishing a record, of their existence and its modes.

As Dr Caruso states:

In establishing this record, the practice of exhuming the remains of Aboriginal people in the name of ‘science’, and the sickening exercise of macerating the bodies of Aboriginal people in the name of ‘science’ was performed unchecked. There are also noted instances where the bodies of Aboriginal people did not reach the stage of burial including that of Tommy Poltpalingada Booboorowie Walker.

‘There is no doubt that Wyatt was cognisant of what was happening,’ Dr Caruso continues. ‘He wrote:

There was a sincere desire, on the part of the settlers in general, to ameliorate the moral and physical condition of these degraded specimens of humanity; and that feeling, coupled with a natural curiosity to search into the mysteries of their origin, and their present status, induced many persons to make them the subject of careful study.

Dr Caruso outlines that:

While Stirling was found to be involved in many morally bankrupt practices after Wyatt’s death, it is likely their close association meant Wyatt still had knowledge of these practices occurring.

As Dr Caruso concludes:

And we are left with a union or association between… individuals, men with absolute power over the powerless dispossessed. Men of privilege whose raison de vivre was to cement their names in the annals of colonial history and build legacies on the bones and ashes and land of Kaurna Meyunna and all Aboriginal people in the ‘state’. Men for who the dismembering of Aboriginal bodies in the name of science was normalised… Edward Charles Stirling and William Wyatt.

Source: Caruso, J.L. (2023), Nala-alati Pinti Miyurna pudni. William Wyatt: From Plymouth to Adelaide and the Infant Colony of South Australia on Kaurna Yerta Pangkarra – Tarntanya the land of Kaurna Meyunna.